This article is extracted from a presentation I held at the Ubisoft Design Summit 2021.

Time is your enemy

|

Over my career, I have acquired technical skills to prototype features by myself, and to demonstrate their purposes with playable content. I had the opportunity to design and script combats and AI systems for multiple AAA projects. However, I also spend a lot of time developing side projects on Unity. Prototyping your own games is great experience – but there are traps that you should avoid. The most important one that I learnt over the years is "time is your enemy". The fact is that creative people tend to dream big – too big. Myself, I used to start the development of very complex prototypes that would have taken me years to implement. Yet, the longer a production is, the more likely you drift away from your original concept. And the more you drift away, the longer the production becomes. At the end, you may suffer from a fatigue that is characterized by a loss of motivation, long breaks of multiple weeks, and the feeling your project turns into a chore. It happened to me multiple times. Hopefully, I've learnt from these experiences, and this is what I woud like to share today. As you will see, these methodologies can be applied to larger prods – but you shouldn't refrain from using them because "you just work on prototypes". |

|

Have a roadmap

|

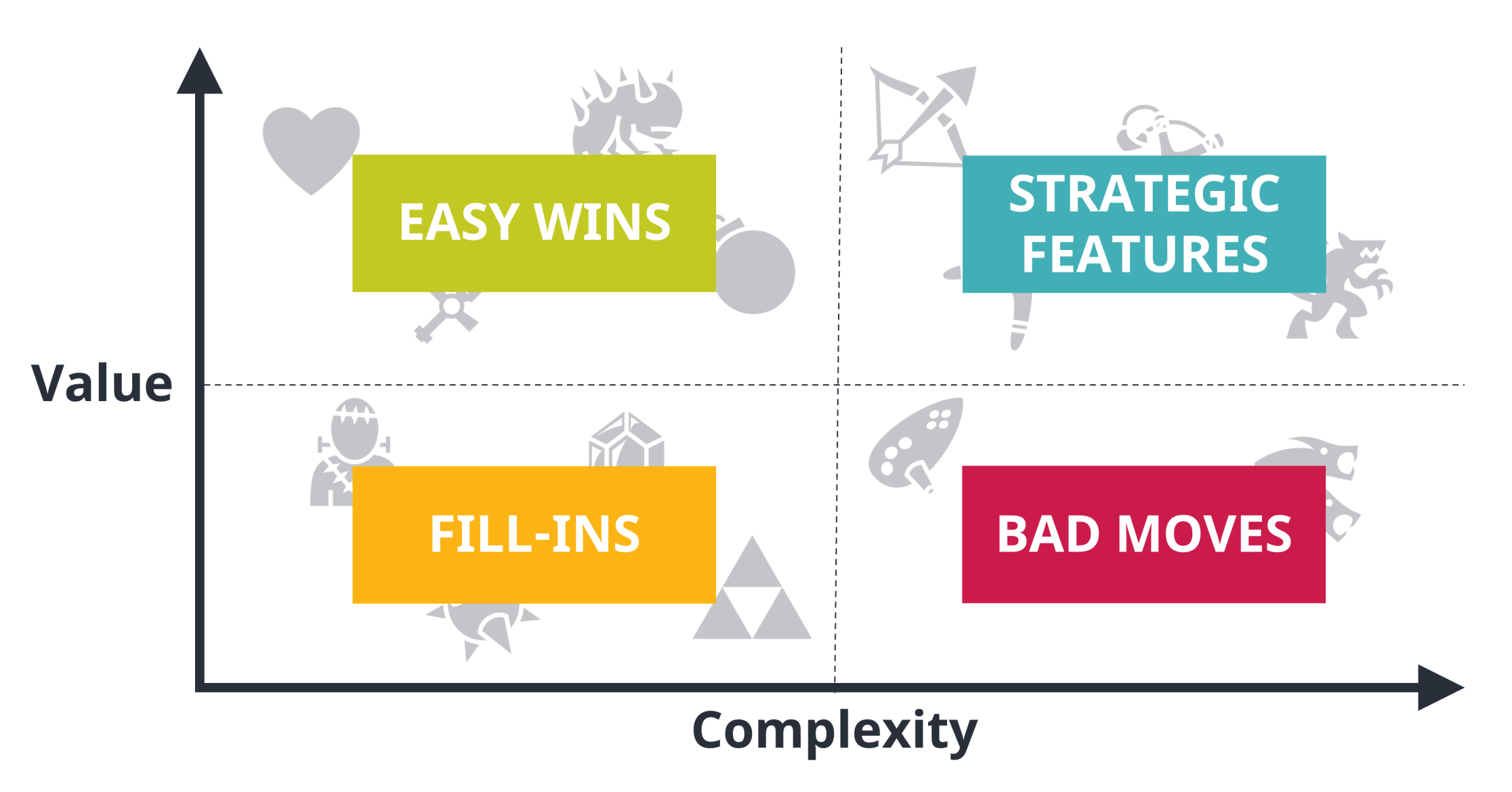

My first advice is to have some kind of roadmap. You need to have a clear idea what you want to achieve, and how long it would take to achieve it. This is a step you really shouldn't underestimate, and I would recommend to always put your roadmap on paper. Ideally, you should stay focused on a core experience that you could achieve in less of a year. I also always take the time to properly look in the editor – before assessing the complexity and value of the features I would like to implement. From there, I break them down into 4 groups:

|

|

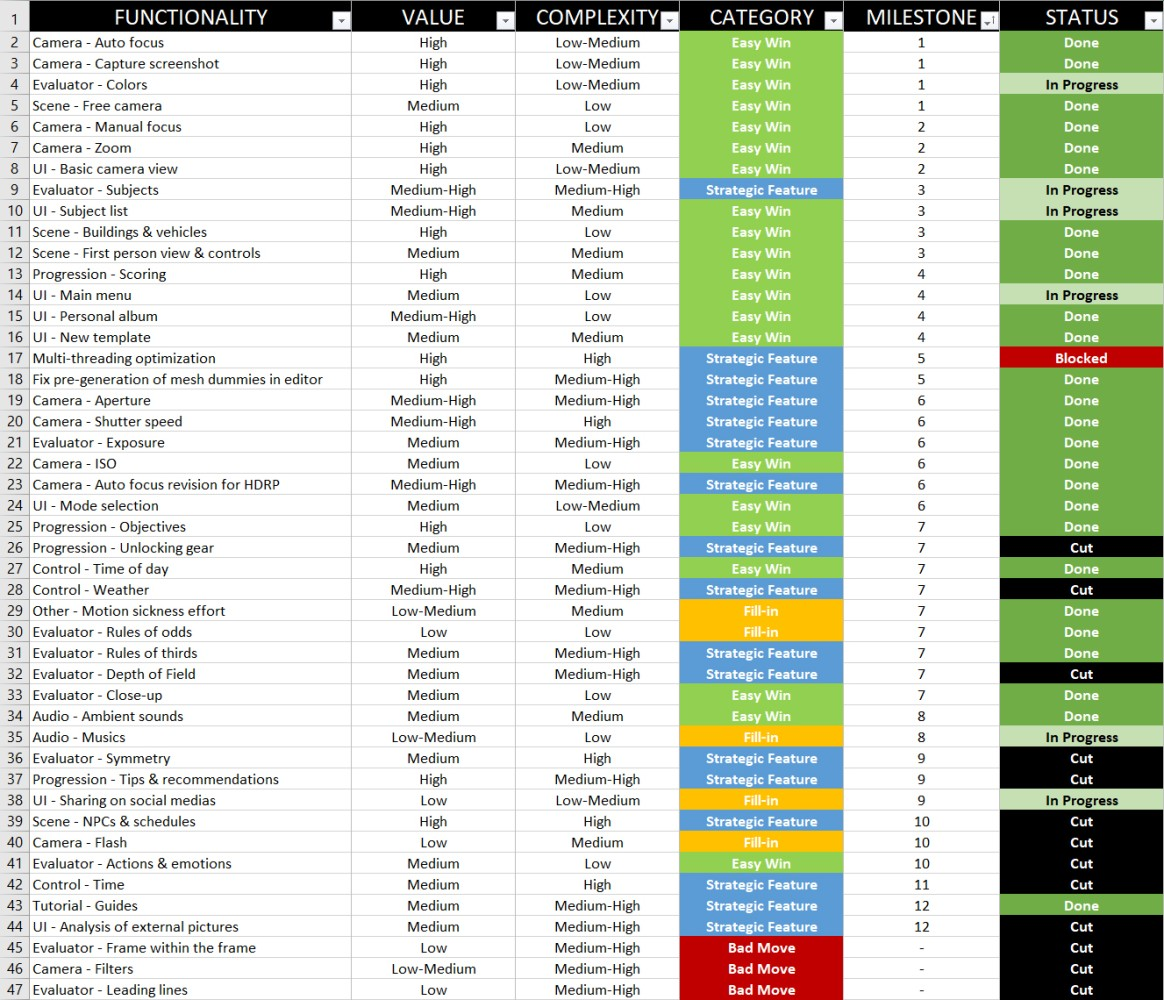

Here the breakdown of Picturesque - a concept that revolved around the gamification of the photography. It’s a pretty simple Excel file that I used for tracking dependencies and my overall progress. I re-ordered items many times over the production – as I was experimenting with new mechanics, and facing unexpected challenges.

As you can see, I’ve cut a lot of content at the end of the production. I could have spent few additional months to implement these features – but I had other plans, and I felt absolutely no frustration while cutting them.

That's the whole point of having a roadmap: prioritizing the features, reaching MVP as soon as possible, and having the freedom of experimenting any other mechanics afterwards. Or not. Once your prototype is solid enough to demonstrate the potential of your concept, you will be able to stop working on the project as soon as the first signs of fatigue show up.

Use time-savers

My second advice is to use as many time-savers as you can. You should have fun and focus on the creation of the gameplay itself – nothing else is worth your time. Repetitive or complex tasks can affect your morale, and you shouldn't feel like "cheating" if you find ways to skip them.

First of all, other developers have probably tried to implement the features you are looking for, and most of them are kind enough to share the code they used. Even if their code snippets don’t provide you with all the functionalities you need, analyzing them can help you understanding the overall logic to follow, the pitfalls to avoid, and you could even improve your own coding. Here a couple of examples.

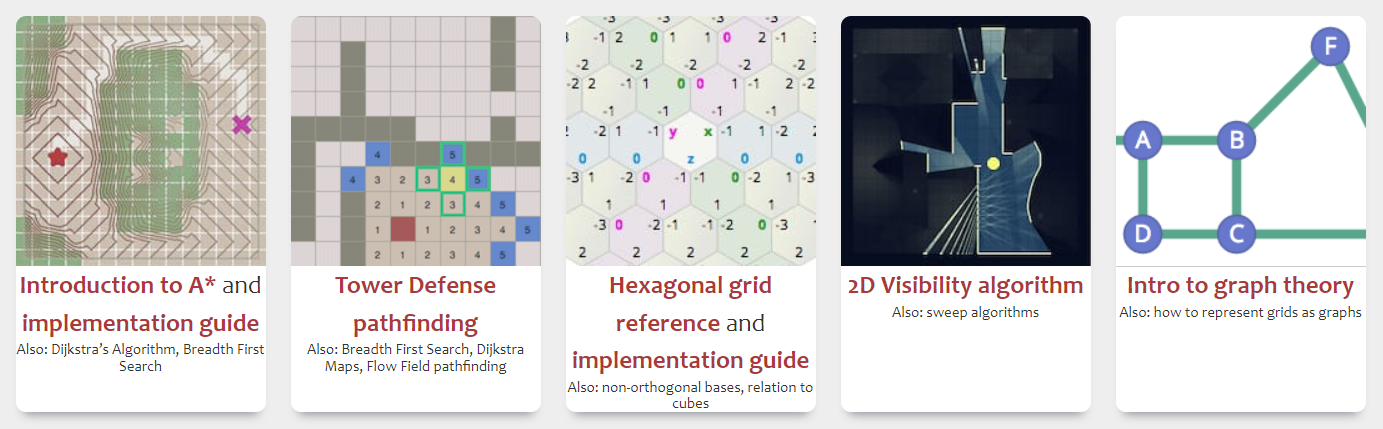

Red Blob Games

Red Blob Games is a website I used for many of the prototypes I worked on. Amit Patel experiments with all kinds of features such as AI pathfinding, hexagonal grids, polygonal maps generation, 2D visibility algorithms... He shares his entire code, and he explains his discoveries in an interactive and very enjoyable way: the website is both educational and inspiring. I always keep a look at it, and I sometimes brainstorm concepts from the tutorials themselves.

Second Tab

My photography concept featured the extraction and analysis of color harmonies. At some point, I realized that “maybe I should sort the colors in a specific way”. I had absolutely no idea where to begin. So I Googled it, and I found this article where Alan Zucconi explains the whole process to sort colors in a smooth and consistent way. This is exactly what I was looking for, I've learnt many things about colors, and it only took me few hours to implement the solution.

|

If you can afford it, I also highly recommend buying assets instead of creating your own. Of course, you will save a lot of time - but their greatest value is to compensate your lack of expertise in specific fields. In my case, well… Let’s just say I’m not an artist :). Hopefully, the store is full of amazing assets. Buying characters and environments is an excellent way for me to stay motivated, to improve the signs & feedback, and to pitch concepts that look more tangible and closer to publishable games. The package beside is one best assets I’ve ever bought: Fantasy Heroes: Character Editor. It’s a huge collection of pieces of gear that can be equipped on a pre-animated skeleton. You create plenty of different characters in few clicks, and it only costs 30 USD – which is very inexpensive for the quality of the asset. This is all-the-more interesting that such assets can be reused across multiple projects. In this case, I used the package in 3 different games. |

I always think about that twice before purchasing anything, so I could minimize my expenses - and save some time by reusing systems that I already know. The same goes for tools that can greatly improve your productivity. They can decrease the complexity of the strategic features enough to turn them into easy wins, and you can even consider implementing features that you would have discarded otherwise.

Finally, you shouldn’t hesitate to take shortcuts – especially if your objective is to prove a concept works and not to publish an actual game. So, if you think a feature is too complex to implement, then just fake it enough for players to foresee its value. Likewise, you can hack functionalities to quickly assess if a feature works as expected – before finding ways to properly implement it.

However, this is not something you should repeat on a casual basis: the more often you hack functionalities, the more rigid and instable your prototype becomes. That’s why you should often take the time to refactor and consolidate your code.

Communicate

|

My third and last advice is all about communication. Some Designers are afraid of early feedback, or that someone would steal their ideas. However, feedback is always valuable – and the earlier you realize you could improve your concept, the less time you waste. The truth is that your concept is probably not that original: many people in the world already had the same idea, and half of them develops it as we speak. And even if someone else has already achieved what you aim for, it doesn’t mean you couldn’t try by yourself and learn takeaways from your own experience. Sharing your progress after each milestone is a great way to stay motivated all along the project. You may not have a lot to share – but it emphasizes all the small wins you achieve, and you may receive a useful feedback from your community, your coworkers, your friends, or even your family. You should also feel free to ask for help as often as necessary. Like I previously said, other developers probably know the solutions you need – and getting advice from them can be a real game changer. This is one of the reasons why you should develop your prototypes on an engine with a strong community (such as Unreal or Unity). |

|

Talk to your HR partner

Here few warnings about your legal obligations. Most contracts in the industry prevent employees from working on side projects as they could be considered as a direct competition. However, you can sign clauses that have 2 objectives:

- Free your employer from any responsabilities regarding the content of your games

- Ensure that you develop them out working hours, without using your workstation and any software or knowledge that belongs to the company

To be honest, it’s quite hard as Game Designers to prove you didn’t use knowledge you have learnt in your company. Thankfully, Ubisoft (my employer) is pretty lenient on this topic, and I went through this process multiple times without any issues.

Note that there may be additional terms according to the studio or the country you work from. This is the reason why you should pro-actively contact your HR partner to discuss about your projects together. You may be tempted to secretly work on them – but it would constitute a direct violation of your contract, and there may be consequences. It would be even more a shame that you would refrain from sharing any content and getting proud of your achievement.

Summary

|

You need to have a roadmap: not something very detailed – but at least put on paper what you want to achieve, and how you plan to do so. Use as many time-savers as possible: look for references, buy assets, invest in tools, and take shortcuts – as long as you’re not building a house of cards. Communicate: join a community, ask for help, and share your progress every time you achieve a small win. If you already have an idea, just do it! Designing concepts, implementing them in an engine by yourself, and proving they do work with playable content – is a great experience I would recommend to anyone. It’s fun, rewarding, and you can even learn takeaways for your everyday life as a Game Designer. |

I hope you enjoyed the read. Here few wishlists from the Unity Asset Store to inspire you: |